boy, snow, bird

Helen Oyeyemi’s prose is remarkable, because it often manages to be simultaneously literal and figurative. At times I felt like I was in someone’s dream:

Sometimes mirrors can’t find me. I’ll go into a room with a mirror in it and look around, and I’m not there. Not all the time, not even most of the time, but often enough. Sometimes other people are there, but nobody ever notices that my reflection’s a no show. Or maybe they decide not to notice because it’s too weird. I can make it happen when I move quickly and quietly, dart into a room behind the swinging of the door so it covers me the way a fan covers a face.

Weaving fable, streams of consciousness, racial injustice, and family dysfunction, the product is poetic and lovely and more than a little melancholy. That there is, in my eyes, an unneeded twist at the novel’s end does not take away from its beauty or from its final note of hope.

the teacher wars: a history of America’s most embattled profession

The authors of Disrupting Class describe the goals of education in this country as:

- Maximize human potential.

- Facilitate a vibrant, participative democracy in which we have an informed electorate that is capable of not being “spun” by self-interested leaders.

- Hone the skills, capabilities, and attitudes that will help our economy remain prosperous and economically competitive.

- Nurture the understanding that people can see things differently—and that those differences merit respect rather than persecution.

For me these ring true, in terms of my experience of my own education, of my values for our nation’s children, and of my hopes for my own work as a teacher. Nevertheless, it’s not clear that it is possible to succeed at all these goals at once, or even just one of them.

Dana Goldstein‘s history of teaching in the United States shows the roots of these goals and how they played out over time in our public education system. It’s a fascinating look at the evolution of the profession and the expectations we have of our schools.

Goldstein is decidedly sympathetic to teachers, who often feel trapped in an at least three-sided vice of parents and students, administrators, and governmental mandates — many unfunded. Read The Teacher Wars if you want to understand some of that feeling and how teaching got to be that way. You might also gain insight on conflicts between teachers’ unions and school boards, between neighborhoods and education reformers, between testing and accountability, and other education-related controversies.

Educational culture in this country does not have to be the way it is. Reading this book will help you understand it better. And that should be the beginning of changing it for the better.

books I’d like to be reading

In no particular order:

The Teacher Wars — Dana Goldstein (I’m about 3/4 of the way through, but haven’t found the time to finish.)

Creative Schools — Ken Robinson and Lou Aronica

Thinking, Fast and Slow — Daniel Kahneman (I’m somewhere in the middle of this brilliant book.)

Three by Cain — James M. Cain (I’ve finished one of the three short novels in this compilation.)

For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood . . . and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education — Christopher Emdin

How We Learn — Benedict Carey

The Underground Railroad — Colson Whitehead

How to Win Friends & Influence People — Dale Carnegie

Mathematics in Western Culture — Morris Kline

Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty — Morris Kline

Something by Elmore Leonard

The Round House — Louise Erdrich

Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports are Played and Games are Won — Tobias Jacob Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim

Christmas 2017, Stevenson Ranch, CA

My soon-to-be 10 year-old nephew wanted to be sure that the adults in the house knew who the milk and cookies were for.

the orphan master’s son

Adam Johnson tells this story of love and identity inside an amazingly real-feeling North Korea, neither glossing over nor glorifying atrocities and human rights violations. Instead, he immerses the reader in a culture that feels upside down – where children clean chemical vats and adults disappear for days, conscripted off city streets to work in rice paddies; where parents teach their children that, even though sometimes you have to denounce each other publicly, you’re still holding hands inside; where a father and husband can be killed and replaced by a stranger overnight, and the family will barely acknowledge the change. Always, on every street and in every home, loudspeakers tell the “Dear Leader”-approved news and warn of imminent invasion by the decadent Americans. Disconnecting your loudspeaker is a serious offense; citizens are encouraged to rat out their neighbors. After all, something may be wrong with the speaker, and you wouldn’t want them to miss an emergency announcement.

This is a powerful, sad, and deeply affecting novel with moments of transcendent beauty. It reminds me of why I loved books in the first place.

top novels

New addition: The Orphan Master’s Son (#11), by Adam Johnson

1 One Hundred Years of Solitude – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

2 Beloved – Toni Morrison

3 To the Lighthouse – Virginia Woolf

4 Mrs. Dalloway – Virginia Woolf

5 Molloy – Samuel Beckett

6 Lolita – Vladimir Nabokov

7 Underworld – Don DeLillo

8 Middle Passage – Charles Johnson

9 White Noise – Don DeLillo

10 Middlemarch – George Eliot

11 The Orphan Master’s Son – Adam Johnson

12 Wuthering Heights – Emily Bronte

13 Suttree – Cormac McCarthy

14 Housekeeping – Marilyn Robinson

15 Love in the Time of Cholera – Gabriel Garcia Marquez

16 The Brother’s Karamazov – Fyodor Dostoyevsky

17 The Plague – Albert Camus

18 Heart of Darkness – Joseph Conrad

19 Darkness at Noon – Arthur Koestler

20 Lord Jim – Joseph Conrad

21 The Poisonwood Bible – Barbara Kingsolver

22 The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald

23 Native Son – Richard Wright

24 All Quiet on the Western Front – Erich Maria Remarque

25 Jane Eyre – Charlotte Bronte

26 On the Road – Jack Kerouac

27 The Invisible Man – Ralph Ellison

28 Ceremony – Leslie Marmon Silko

29 Wolf – Jim Harrison

30 Narcissus and Goldmund – Herman Hesse

31 The Master and Marguerita – Mikhail Bulgakov

32 Blindness – Jose Saramago

33 A House for Mr. Biswas – V. S. Naipaul

34 Written on the Body – Jeanette Winterson

35 The Glass Bead Game (Magister Ludi)- Herman Hesse

36 The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck

37 Blood Meridian – Cormac McCarthy

38 The Intuitionist – Colson Whitehead

39 The Bone People – Keri Hulme

40 Of Mice and Men – John Steinbeck

41 The Tin Drum – Gunter Grass

42 Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen

43 One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich – Alexander Solzhenitzen

44 Gravity’s Rainbow – Thomas Pynchon

45 Motherless Brooklyn – Jonathan Lethem

46 Americanah – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

47 The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao – Junot Díaz

48 1984 – George Orwell

49 The Fortress of Solitude – Jonathan Lethem

50 To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

51 Old School – Tobias Wolff

52 The Uncomfortable Dead: (what’s missing is missing) – Paco Ignacio Taibo II & Subcommandante Marcos

53 Huckleberry Finn – Mark Twain

54 Mao II – Don DeLillo

55 Catcher in the Rye – J. D. Salinger

56 A Confederacy of Dunces – John Kennedy Toole

57 The Scarlet Letter – Nathaniel Hawthorne

58 Frankenstein – Mary Shelley

59 Anna Karenina – Leo Tolstoy

60 As I Lay Dying – William Faulkner

61 The Red Badge of Courage – Stephen Crane

62 A Tale of Two Cities – Charles Dickens

63 Neuromancer – William Gibson

64 For Whom the Bell Tolls – Earnest Hemingway

65 Generation X – Douglass Copeland

66 Brave New World – Aldus Huxley

67 The Chosen – Chaim Potok

68 Doomsday Book – Connie Willis

69 Corelli’s Mandolin – Louis De Berniere

70 Fall on Your Knees – Ann-Marie MacDonald

71 Middlesex – Jeffrey Eugenides

72 The Dog of the South – Charles Portis

73 All the Pretty Horses – Cormac McCarthy

74 Dr. Zhivago – Boris Pasternak

75 The Crying of Lot 49 – Thomas Pynchon

76 Fahrenheit 451 – Ray Bradbury

77 Gorky Park – Martin Cruz Smith

78 White Teeth – Zadie Smith

79 The Stone Canal – Ken MacLeod

80 Schizmatrix – Bruce Sterling

81 The Left Hand of Darkness – Ursula K. LeGuin

82 The Loved One – Evelyn Waugh

83 The Metamorphosis – Franz Kafka

84 The Fall – Albert Camus

85 Vineland – Thomas Pynchon

86 Straight Man – Richard Russo

87 A Small Death in Lisbon – Robert Wilson

88 Disgrace – J. M. Coetzee

89 Kindred – Octavia Butler

90 The Road – Cormac McCarthy

91 The Palace of Dreams – Ismail Kadare

92 The Street – Ann Petry

93 The Feast of Love – Charles Baxter

94 Fear of Flying – Erica Jong

95 Clockwork Orange – Anthony Burgess

96 The Old Man and the Sea – Earnest Hemingway

97 The Star Fraction – Ken MacLeod

98 He, She, and It – Marge Piercy

99 The Dispossessed – Ursula K. LeGuin

100 The Shipping News – E. Annie Proulx

101 The Parable of the Sower – Octavia Butler

Okay, I admit I didn’t want to drop The Parable of the Sower all the way off my list, so this list becomes “top novels,” instead of “100 top novels.”

This begs the question, why not add more than 101? Why not make it 200? or 500? So far, the answer is that I don’t want to spend the time on that. Maybe in the future.

best practices for teaching with emerging technologies

Michelle Pacansky-Brock had my attention from the first paragraph of the introduction, where – in response to comments like, “Students today are so unmotivated,” “Students today don’t care about anything but their grades,” and “Students today feel entitled and aren’t willing to work hard” – she asks, “Are our students the problem? Or is it our [higher education’s] instructional model?” By shifting the responsibility to us, teachers and colleges, she wins an ally with me.

The foundation of her work is the idea of moving from “teaching to learning,” a phrase taken from a 1995 article by Barr and Tagg that, in part, means students learn more when they are active participants in their learning, rather than passive listeners to their professors. In addition, Pacansky-Brock leverages John Medina’s Brain Rules, focusing on three that she believes are “relevant for 21st-century college educators”: exercise boosts brain power; sensory integration; vision trumps other senses.

Not only, she argues, can technology help make learning more “brain-friendly” through strategies like those, it’s also the language that today’s college student speaks. Citing numerous statistics – like, 85% of 18-29 year olds in the U.S. have a smart phone – Pacansky-Brock supports the idea that “’online’ is a culture to young people. Yet to most colleges, it is a delivery method.” In sum, teaching with emerging technologies makes sense on a lot of levels and most colleges are behind the curve.

What follows is mostly practical advice for getting on the technology bus, based in experience and experiment. As a classroom teacher at both community college and state university levels, Pacansky-Brock been willing to try a lot of things. Readers benefit by learning from both her successes and failures.

Chapter one discusses the basics of preparing your students for a participatory classroom that uses significant technological tools. Because “students are trained to expect” a hierarchical classroom environment, “when an instructor embarks upon an instructional model that assumes a flattened relationship between student and instructor, like the flipped model, the must be communicated and discussed so it’s clear to students.” They need to understand why you are doing what you’re doing and how the pieces fit together to create the community of learners that you are trying to create.

This first chapter also includes issues like classroom philosophy, community ground rules, student privacy, copyright in the electronic world, and even a bit on the linking versus embedding in your online materials. Chapter two spends more time on participatory pedagogy and some basic tools you can use to foster it. In chapter three, she spends time on the “essentials” – smartphone, webcam, microphone, screencasting software, online content hosting, and more. Chapter four goes into more detail about tools for creating compelling visual content, from infographics to video conferencing to a “liquid” syllabus. Chapter five delves into the tools for participatory learning, including social media, online bulletin boards, online meetings, digital polling, and more on content curation. Through it all, Pacansky-Brock shares what she does, elaborates other options, and discusses the pros and cons of both. Her ideas, tips, and stories make what might seem like a list of apps into something like an annotated bibliography.

The book’s last full chapter is an extended argument for the potential of the internet to innovate and create new and better learning opportunities for students. Pacansky-Brock advocates against using your college’s Learning Management System (LMS) and describes her own evolution on this topic:

When I started teaching online in an LMS, I was disappointed in the quality of the learning environment I had developed for my students and felt constrained by the features available to me. By experimenting with new tools, I discovered different ways of engaging my students and opportunities for being present in their learning. But I still felt the need to use an LMS, largely because of concerns about violating the license for the images included in the textbook I was using, as well as my (former) institution’s expectation for faculty to teach with institutionally supported technologies. I imagine many instructors can relate to that experience.

I certainly can. But there is more. The extensive use of the LMS in higher education, she writes, “may be contributing to a gap between the skills college graduates need and the skills they have.” The LMS provides privacy, control, and less distraction, but it cannot keep up with the speed and scale of innovation on the open internet. Using an LMS also prevents students from developing a professional web presence. In fact, content developed by students during the course disappears when the course is over – essentially, their work inside the LMS is disposable. Working in the open internet can motivate students to produce higher quality work, because after all, “the internet is forever.”

Pacansky-Brock does not think the internet is a panacea for educating students. She sees the advantages and disadvantages of learning through the internet and believes that technology can be used to make learning more human and more participatory. She is thoughtful and thought-provoking – as a teacher, I was constantly taking notes for my own classes, sparked by ideas and stories in the book. I will be referring to it frequently as I continue to refine my teaching practice.

You can find out more at: http://teachingwithemergingtech.com/

the murder of roger ackroyd

Agatha Christie is the master of the mystery novel. In The Murder of Roger Ackroyd she delivers another brilliantly clever plot told in subtle, succinct prose that leads you down every garden path on the way to the surprising resolution. I read this one because it made #1 on the Guardian list of the best Christie novels. It lived up to the billing.

disrupting class: how disruptive innovation will change the way the world learns

Only one of the authors of this book come from an education background. The other two study and write primarily about business. Their idea is to take the insights they have about the way businesses change and apply them to education.

To me, their most useful insight is that big breakthroughs in innovation first develop in a markets that were not previously being served or were being served poorly. In an example they use a few times in the book, the first makers of the minicomputer didn’t try to market their product to the government or businesses that were already invested in mainframe computers. Instead, they marketed to smaller businesses and individuals who could not afford and didn’t have the space for mainframes. Trying to compete with the mainframes directly would have been a losing cause, since the companies that made the mainframes were already good at it and already had large market shares. In addition, even though the first minicomputers didn’t have all the power and functionality of the mainframes of that day, the early minicomputer users were happy with the product because without it they didn’t have access to computers at all. That is, people in new markets are willing to accept some less than ideal circumstances, because they had no service before. As time goes on, and people become accustomed to the new product, they expect higher and higher levels of service — note that minicomputers got increasingly powerful to match those expectations.

The same is true for educational reform. Educational innovators are going to have a very difficult time being successful while fighting against a well-entrenched system. Unless you serve a new market, your innovation is almost certain to function mostly at the edges and to last only as long as you have “extra” money to pay for it. You aren’t going to truly “disrupt” the system.

The book’s authors believe that educational technology can serve previously unserved or underserved markets and eventually change education as we have known it and they believe that the unserved markets are in places like: small schools that cannot afford to offer “enrichment” courses; credit recovery for students who have to take regular classes, too; providing individualized instruction for students who do not learn well in traditional classes.

The authors think the last example is especially important and suggest that, as the software improves, much of school can be transformed into an individualized environment for students, with teachers guiding and assisting as needed — improving education for all students because they are being taught in the style in which they best learn, rather than in the relatively monolithic, one-size-fits-all methods that most schools employ. Based on their observation of disruptive innovation in other areas, they predicted (when they published the book in 2008) that “by 2019, about 50 percent of high school courses will be delivered online.” Whether or not this is accurate remains to be seen, but the vision they provide is of a student-centric learning environment that is enabled by technology, while remaining very much human and humane.

Disrupting Class is at it’s best when talking about the potential for change and how that change could happen. It’s much less compelling when talking about educational research and policy. I appreciate the authors’ vision, if not always their specific recommendations for moving toward it.

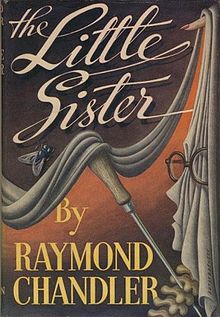

the little sister

The Little Sister is all atmosphere and attitude. Chandler’s protagonist, Phillip Marlowe, more observes the action than drives it forward. He is pessimistic and tired, even as he cracks wise at any opportunity. Women throw themselves at him, but he can’t seem to marshal the energy to do more than kiss them once or twice and keep up the banter. He’s a step behind every murder, and the loosely knit plot keeps the reader feeling even further behind. (I repeatedly found myself looking back in the book to see what I’d missed, only to realize that I didn’t miss anything; the details weren’t there to notice.)

At the same time, having just read The Maltese Falcon, it was hard for me not to notice that many of the plot devices were similar. If, as some commentators suggest, Little Sister is partly a response to Chandler’s experience in the movie business, I think it’s also paying homage to Hammett’s classic.